How to Host Remote MCP Servers in Azure

How to build, scale and host your own Remote MCP Server Platform in Azure

In this blog I want to cover a hot topic in the industry which is around this word MCP, if you haven't been living under a rock this last year it's probably a term you've seen quite a lot, but what actually is it? And how does it actually work?

We are going to dive into this Protocol and explore how it works and some of the differences between Local and Remote MCP's. And also cover some work I have recently done for my company around building a remote MCP Platform on Azure.

What is MCP?

The Model Context Protocol (MCP) is an open standard that allows AI assistants like CoPilot/Claude Code to connect to external data sources and tools. Think of it as a universal adapter that lets your AI tools speak the same language as your databases, APIs, and services.

Local MCP vs Remote MCP Servers

Local MCP: Local MCP servers are quick and efficient for personal use, a local MCP will always be configured on your own machine and will use something called STDIO Transport to work. They are a good choice for some use cases however people using them can come across risks of using malicious or non-secure MCP's.

Another disadvantage is also take for example you have 50 engineers inside of your Platforms team, 50 users want to use MCP servers to help speed up their day-day work. This requires each of those 50 engineers to manually configure them on a per individual basis. Which is time consuming and requires some knowledge around how they work spending time on ReadMe files trying to figure it out.

Remote MCP: Remote MCP servers work slightly different than local in terms of their transportation methods, instead of STDIO they use a different protocol called HTTP/SSE.

The advantage of using Remote MCP's are that they are accessible from anywhere, easy to use for large Platform teams meaning instead of 100 developers having to tediously setup the same local config on their machine x100 times they simply connect once and the rest is handled.

However it comes with a trade off, in that remote MCP's can be tricky to configure and especially difficult to secure and run. But that's where this blog post teaches you how to do it.

The Problem We're Solving

Many organisations want to leverage MCP's to help their organisation/colleagues who are using AI to connect to external systems. However they all face the same fundamental issues and troubles, some of which are:

- Security: There are lots of malicious untrusted MCP servers which anyone can unknowingly trust and run locally on their machine which can lead to data breaches etc

- Consistency: Each developer might configure their server differently or have trouble setting it up

- Access Control: No centralised way to manage who can access what tools in an MCP

- Scalability: Can't share one server across a whole Platforms team

- Auditing: No centralised logging of what queries are being run/endpoints being access by whom

This Azure MCP Platform Pattern I have designed it to combat and solve all of these problems above by providing a secure, centralised, and observable way to host MCP servers that your entire organisation can use.

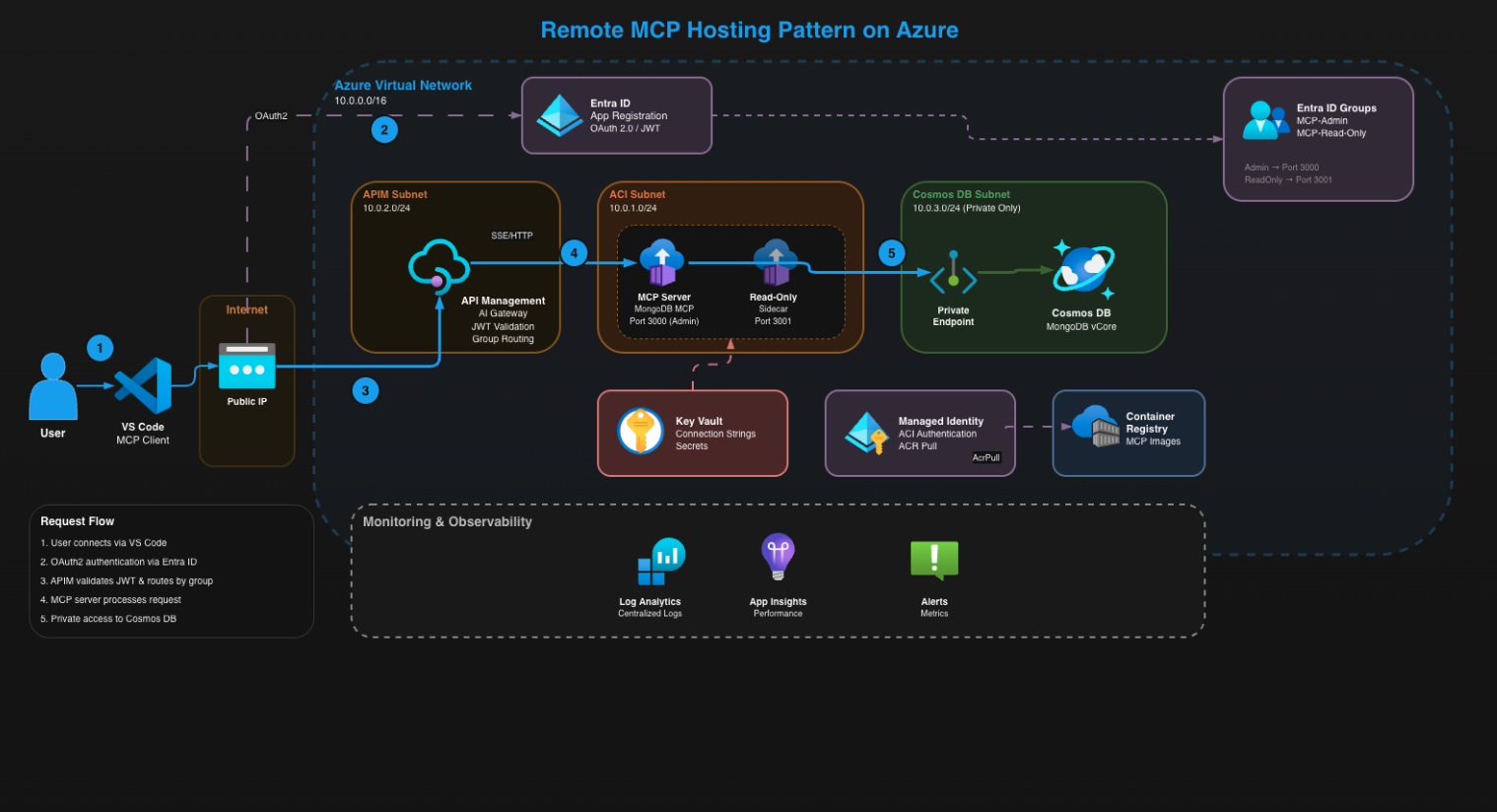

Architecture Overview

Let me walk you through how we've designed this platform. The architecture follows several cloud-native patterns that work together to provide a secure and scalable solution.

The architecture consists of some enterprise services such as APIM and CosmosDB for MongoDB. Let me explain the setup

You will find the repository for this MCP Pattern here, feel free to share it and deploy it for yourself - MCP Pattern Code

Let's break down each component.

1. Azure API Management (APIM)

APIM is the first point of entry for our architecture, when a user opens up their Co-Pilot/MCP Inspector to connect to an MCP they will hit the APIM hostname with a special endpoint called /mcp/mongodb which will direct the users to hit the Public IP address of the APIM instance.

APIM is configured in something called external mode which means it has two IP addresses, one public for the requests and another private for the backend instances which we will cover later.

Next is where the first security check happens for OAuth 2.0 authentication: APIM looks at the incoming request and checks for a valid OAuth 2.0 bearer token in the Authorisation header. This token gets issued from Entra through an App Registration we created.

The best practice when handling authentication for MCP is ALWAYS embedding the access token within the authorisation header as documented here - How to make authenticated requests

If there's no token, or if the token is invalid or expired, the request stops right here - APIM returns a 401. And the request will never touch our backend.

If there is a valid token, APIM validates that token against Entra ID, checks the signature, verifies it hasn't expired, and critically - checks for an Entra ID groups claim. This is all configured within the APIM Policies which you will find in the repository.

We've configured APIM to require that users are members of a specific Entra ID security group. If the user's token doesn't contain this group ID in the groups claim, access is denied immediately.

This means access control is centralised in Entra ID - we can add users Object ID's inside the tfvars file to dictate who gains Admin/Read Only access to the MCP Servers. I'll explain how the ReadOnly/Admin access works if you stay tuned!

Only after all these checks pass does APIM allow the request to proceed. APIM lastly logs this request to our Log Analytics Workspace - capturing who made the request, when they made it, what endpoint they hit, response time, and success or failure status.

If you want to learn everything about the security mechanisms behind this solution you can see this guide from the official MCP page - Understanding Authorisation in MCP

2. Azure Container Instances (ACI) — The MCP Server Host

Once the request is authenticated, APIM routes it to the appropriate backend. In our case, we're running a MongoDB MCP server, so APIM looks up the backend URL we configured during deployment. This is where the request crosses from the public internet into our private Virtual Network. APIM uses its internal network interface to send the request to the Azure Container Instance running in the ACI subnet.

Notice what's happening here: the Container Instance does NOT have a public IP address. It's completely isolated within our Virtual Network. The only way to reach it is through APIM. Even if someone knew the private IP address, they couldn't reach it from the internet because Network Security Groups are blocking all inbound traffic except from the APIM subnet.

Quick note on how this container even got deployed: The container image is stored in Azure Container Registry, this gets created and deployed at runtime in the Pipeline. The Container Instance uses a user-assigned managed identity to then pull that image. This means zero credentials, zero passwords - just passwordless authentication handled by Entra ID. The managed identity has only the AcrPull role as that's the only permission required which in turn follows the best practice of least privilege.

The MCP server needs a connection string to reach the database. We've stored this connection string securely in Azure Key Vault, and during container startup we injected it as a secure environment variable. The containers read this variable and uses it to connect to the database. The connection string is randomly generated at run time which adds an extra level of security.

NOTE: ACI is an interesting choice from an architecture perspective, most people would probably choose something along the lines of AKS, Container Apps, or even a simple App Service Plan. However I will explain why I choose ACI... there is method to the madness

We also have ACI running in a sidecar deployment. The reason for this is as great as MCP's are, they can be highly destructive and catastrophic if the wrong person gets access to the right tools. Through this setup we have an efficient yet effective architecture which can demonstrate full CRUD capabilities.

3. Azure Cosmos DB (MongoDB API) — The Data Layer

So we've covered how requests get authenticated through APIM and routed to our Container Instance. But where does the data actually live? That's where Cosmos DB for MongoDB vCore comes into play.

The database has zero public internet exposure. You cannot reach this database from the internet - there's no public IP, no public endpoint, nothing. If you tried to connect from your laptop, you'd get nowhere. So how does our container actually talk to the database? Private Endpoints.

We've created a Private Endpoint to allow the connections to run seamlessly from within our Virtual Network directly into the Cosmos DB service. The Container Instance connects to this private IP, and the traffic never leaves Azure's backbone network.

But wait - the container needs to actually find this private IP. That's where Private DNS comes in. We create a Private DNS Zone privatelink.mongocluster.cosmos.azure.com and link it to our Virtual Network. Then we add an A record that maps our cluster name to the private IP address. When the container tries to resolve the database hostname, it gets the private IP instead of a public one.

The flow looks something like like this:

Container Instance → Private DNS Resolution → Private IP (10.0.3.x) → Private Endpoint → Cosmos DB

Now for the credentials. The database still needs authentication - we're using MongoDB's native SCRAM-SHA-256 mechanism. But here's the thing: we never hardcode passwords.

Terraform generates a secure 32-character password that's randomly generated at run time and then stored inside of the KeyVault.

What you will also notice is that we're connecting to port 10260 (the vCore MongoDB port) over TLS, using the private IP from our Private Endpoint. This means even if the connection string somehow leaked, it would be useless - that IP address only exists within our VNet.

Prior to the idea of using the Azure offering for MongoDB, we were using MongoDB Atlas which works slightly differently. It's all web-based and isn't managed inside Azure. So ultimately it's better to have everything under the one umbrella to be managed inside of Azure in this regard.

Ideally we would also liked to have eliminated the username/password dependency and use something like a User Assigned Managed Identity to authenticate instead. However the reason we could not do this is because the mongodb-mcp-server npm package cannot connect to Cosmos DB MongoDB vCore using OIDC/managed identity authentication. To get around this you could opt for a solution such as AKS. But again this was a small PoC like task so it's one to note down for the future!

4. Entra ID Groups & App Registration — The Access Control System

We covered the 3 main services to this architecture, I think it's also worth noting the smaller services as they still hold equal importance to this solution as the bigger ones. The Access control in this architecture is entirely driven by Entra ID. We create two Entra ID security groups at deployment time: MCP-Admin and MCP-Read-Only.

The Admin group grants full access to all 23 MCP tools including destructive operations like insert, update, and delete.

The Read-Only group restricts users to 14 read-only tools - things like find, aggregate, count, and list collections. No write capabilities whatsoever.

Users get added to these groups via their Object IDs in the tfvars file. This means access control is centralised - no hardcoded user lists in application code, no separate user databases to manage. Add someone to the Entra group, they get access. Remove them, access is revoked instantly. It's that simple.

The App Registration is where the OAuth flow happens. We've configured it to include group membership claims in every access token. When a user authenticates, their token contains a groups claim with the Object IDs of every group they belong to. APIM then inspects this claim to determine what level of access they should have.

We've also set app_role_assignment_required to true on the Service Principal. This is critical - it means if you're not explicitly assigned to the app via group membership, you cannot get a token at all. Even if you're in the same Entra tenant, even if you're a global admin, without being in one of those two groups you get nothing. The door is simply closed.

The App Registration also requests the GroupMember.Read.All permission from Microsoft Graph. This allows APIM to perform real-time group membership checks rather than relying solely on what's cached in the token. If someone gets removed from a group, APIM knows about it immediately.

5. The Sidecar Pattern — Admin vs ReadOnly Routing

Here's where the method to the madness of choosing ACI comes in.

MCP servers are powerful - they give direct database access. The MongoDB MCP server has tools like insertOne, updateMany, deleteMany, and even dropCollection. In the wrong hands, that's catastrophic... bye bye database. So we want to enable some users read access for querying and exploration without the risk of a P1 incident. This allows us to sleep at night without worrying about waking up to a whole database gone in the wind.

The solution for this having choose ACI is simple... run two containers in the same Container Group.

The main container runs on port 3000 with full access to all tools. The sidecar container runs on port 3001 with a restricted tool set - only read operations are exposed. Both containers share the same network namespace since they're in the same ACI Container Group, so they both connect to the database using the same connection string. The difference is purely what tools they make available.

APIM handles the routing based on group membership. When a request comes in, APIM extracts the groups claim from the token. If the user is in the Admin group, the request routes to port 3000 on the container's private IP. If they're in the Read-Only group, it routes to port 3001 instead.

This is why ACI makes sense here. We needed two containers sharing the same network, no public IP with proper VNet integration, and simple deployment without Kubernetes complexity. AKS would be overkill for this use case. Container Apps would work but adds unnecessary complexity. ACI gives us exactly what we need - two containers, one private IP, different ports.

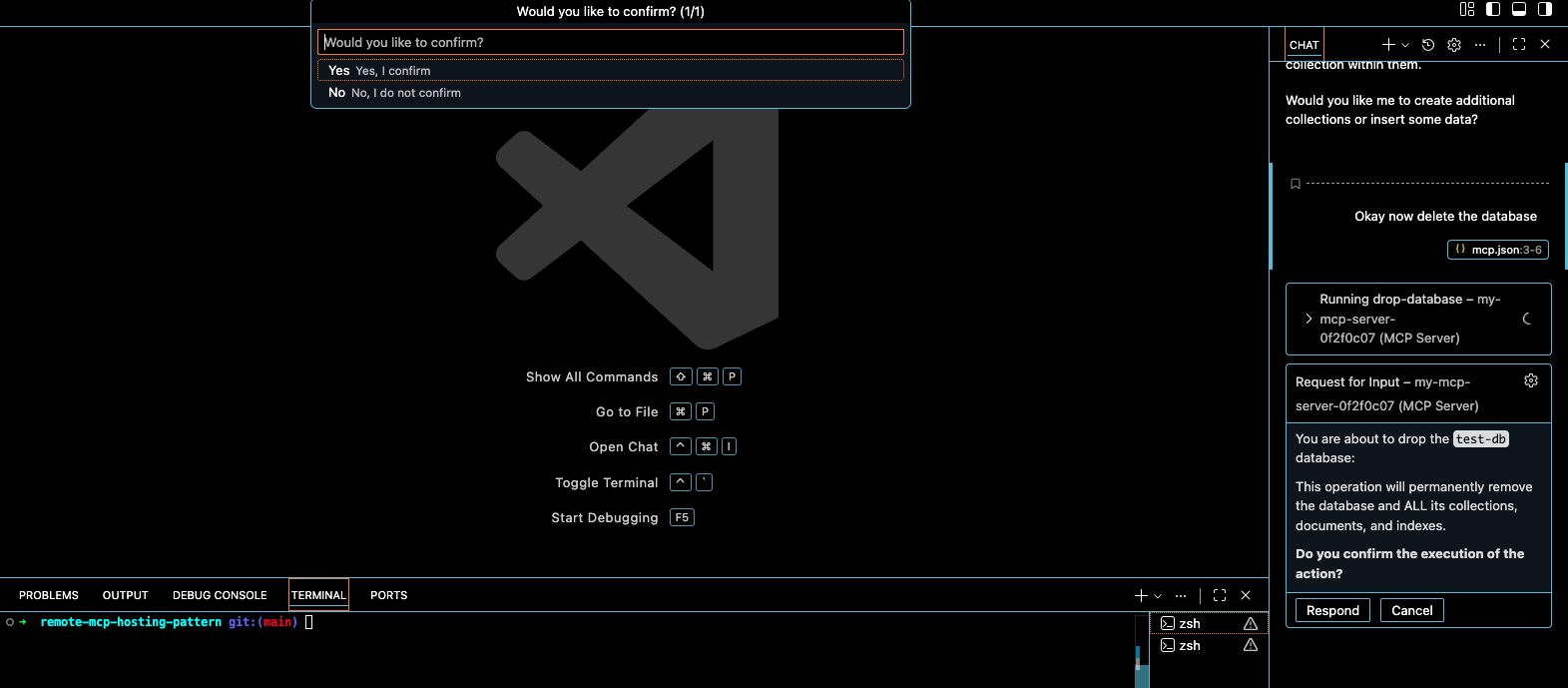

Interesting Note: Inside of the tfvars you will see a line that looks like so:

MDB_MCP_CONFIRMATION_REQUIRED_TOOLS =

This is a special parameter that can be added which will prompt the user twice before making a possibly career ending mistake in dropping a whole document from the DB.

This is what it would look like when a User goes to drop the database. You can see on the right hand side that it prompts first, the secondly at the top it asks again. This is a guard rail that the MongoDB MCP has built in.

Giving credit where credit is due, the MongoDB MCP is very well constructed in this manner. This is the standard that all MCP's should follow.

Below is a nice example of the Admin/ReadOnly group in action from a User POV.

I want you to notice in both videos the following:

- Admin Group has full access to the tool set of MongoDB MCP

- ReadOnly Group has limited tool sets to the ReadOnly tools

Admin Group

ReadOnly Group

6. Virtual Network & NSG Rules — Network Segmentation

The Virtual Network is divided into three subnets, each with a specific purpose.

The ACI subnet is where our Container Instances live. It has a delegation to Azure Container Instances, meaning only containers can be deployed here. The APIM subnet hosts the internal network interface for API Management - this is how APIM communicates with backend services privately. The Cosmos DB subnet exists solely for the Private Endpoint that connects us to the database.

Network Security Groups enforce strict traffic flow between these subnets. The most important rule: only the APIM subnet can talk to the ACI subnet on ports 3000 and 3001. Not VirtualNetwork, not Internet - specifically the APIM subnet CIDR range. Even if something else was running in our VNet, it couldn't reach the containers.

We also allow the Azure API Management service tag to reach port 3443 - this is required for APIM's management plane to function when deployed in VNet mode. And of course, Internet traffic is allowed to hit the APIM subnet on port 443, but only there. That's the only public entry point.

7. Key Vault & RBAC — Secrets Management

Every secret in this architecture lives in Azure Key Vault. The MongoDB admin password, the full connection string, and the Application Insights instrumentation key - all stored centrally and securely.

The password isn't something we create manually. At run time, a cryptographically secure 32-character password is randomly generated. This password immediately gets stored in Key Vault. The connection string is then constructed using the private endpoint IP address and stored as a separate secret. Nobody ever sees these values in plain text during deployment.

RBAC controls who can access what in the Key Vault, and we follow least privilege strictly. The Pipeline Service Principal gets the Key Vault Secrets Officer role. This allows it to create and update secrets during deployment - it needs to write that randomly generated password somewhere after all. But it's scoped only to this specific Key Vault.

The Container Instances themselves have no Key Vault access at runtime. The connection string is injected as a secure environment variable during deployment. This means we don't need the Key Vault SDK in the container.

This layered approach means everyone gets exactly what they need and nothing more. The pipeline can deploy, admins can troubleshoot, and the application can connect to the database - all without any single identity having more access than necessary.

Conclusion

If you made it to the end, thank you for taking 20 minutes of your day to listen to me ramble on about this solution I have created. MCP is the new kid on the block that's here to stay and a protocol that really enables AI Assistants to break down the barriers.

As organisations will continue to adopt the MCP Protocol in their business it's vitally important they take into consideration as good as it can be, it's equally as destructive and harmful if not implemented correctly. This solution is a prime example of how they can start to centrally manage MCP servers securely.

The moral of the story from this architecture is perfect is the enemy of good in that you can definitely implement AKS/Container Apps instead of ACI when you want to onboard multiple MCP Servers. But for this use case of one MCP Server ACI ticked all the boxes when I reviewed the design guide.

LMK / reach out if you have any questions around this!